Kindred Spirits

This issue of Casual Archivist was made in collaboration with New York creative studio Mythology, who are currently at work on a new project about the unruly history of what we call “branding”—not logos exactly, but the ways that symbols, rituals, and visual systems have signaled belonging across cultures and centuries (i.e. no identity guideline fetishization allowed!)

Today’s essay is a preview of the kinds of stories the project will explore, as well as a call for collaborators and pitches. The Mythology team is interested in connecting with designers, historians, writers, and archivists—especially people outside the US—whose research touches on the intersection between design systems and culture. Think: nihilistic sodas, identity systems that turned into protest art, fraudulent makers marks, and anything that kind of reminds you of Dr. Bronner’s. If you have expertise off the beaten path of design history, or if you know of archives, thinkers, or case studies that might fit the brief, the team would love to connect. You can reach out via email to caitlin@mythology.com.

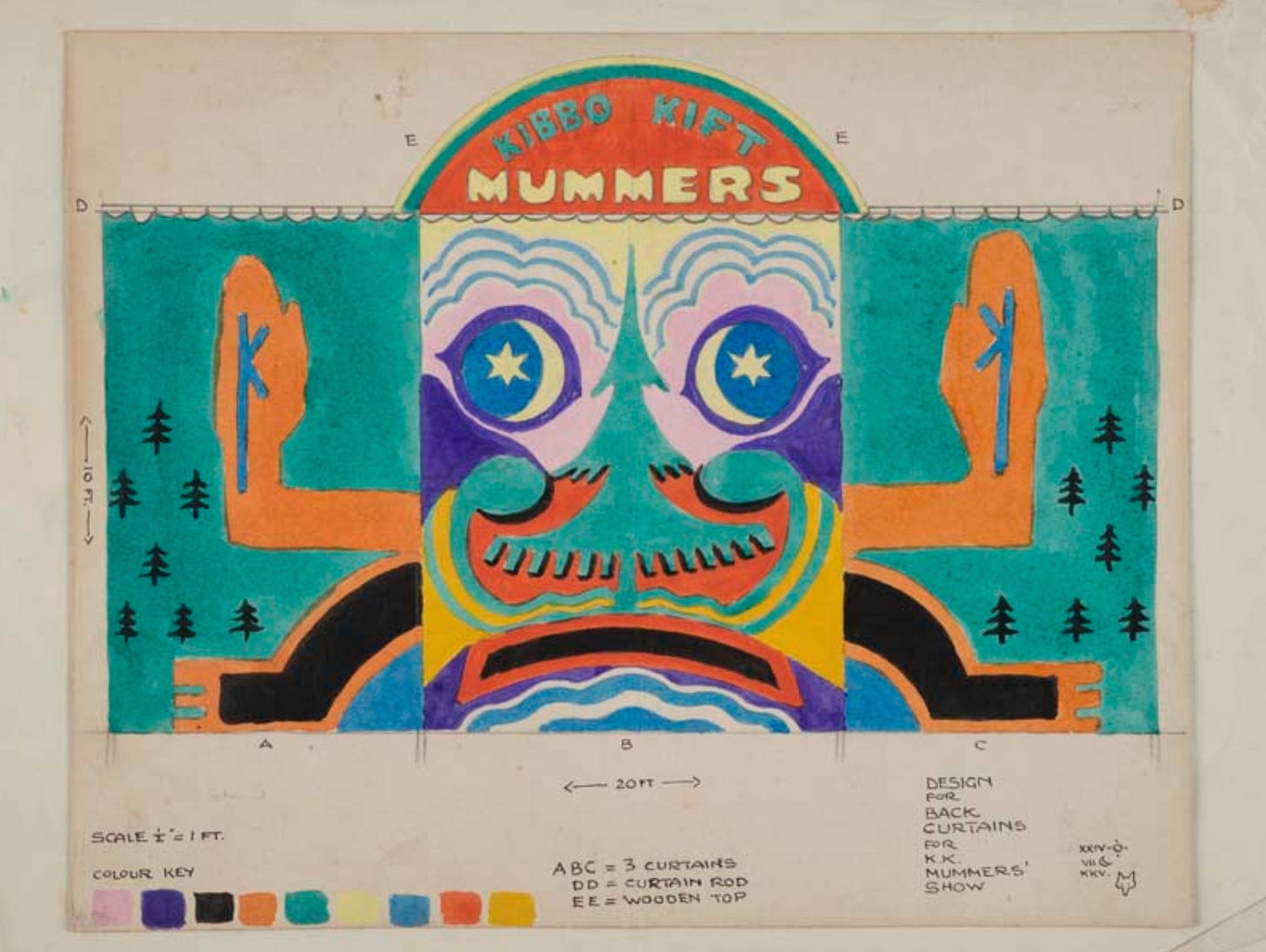

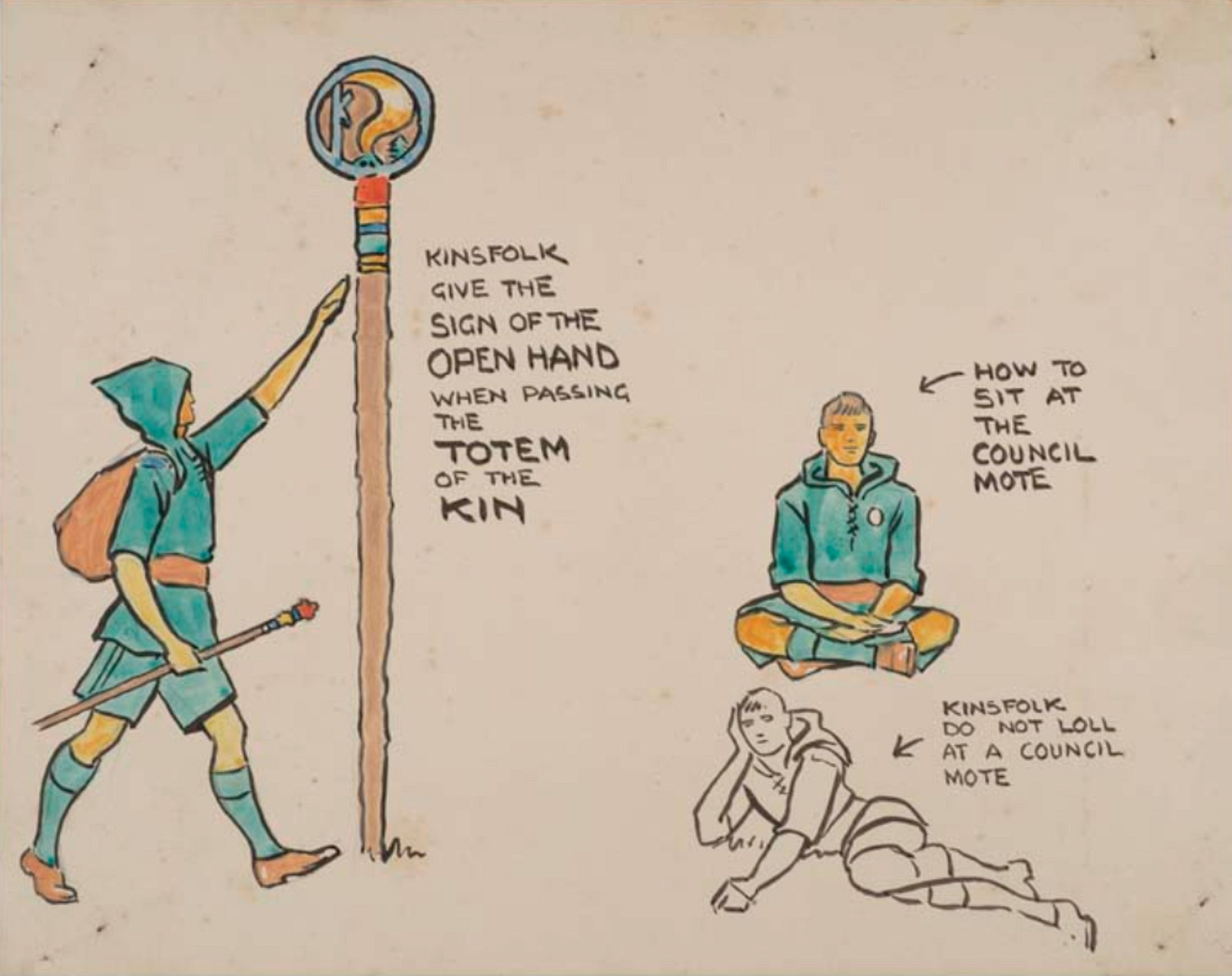

Today’s collection is an archive of materials from the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, a short-lived British youth movement founded in 1920 by John Hargrave, a Utopian polymath described as an “author, cartoonist, inventor, lexicographer, artist and psychic healer.” A former Boy Scout leader himself, Hargrave had grown frustrated with the group—founded in 1907 by Lieutenant General Robert Baden-Powell to drill discipline and patriotism into young men—after experiencing the horrors of World War I firsthand. In response, he set out to create a new, non-militaristic alternative. Where the Scouts were gender-separated, and stressed imperial duty, Hargrave’s co-ed, all-ages group was deliberately progressive, promising self-expression, creativity, and spiritual renewal through craft, ritual, and outdoor life. Members were asked to sign a covenant of pacifist ideals and together performed folk plays, participated in spring hikes, and gathered for Althings, an annual general meeting. Despite the inconvenient overlap between the initials of the group and the US far-right hate group the Ku Klux Klan, the name “Kibbo Kift” actually comes from a Kentish Old English phrase meaning a feat of strength (specifically, hoisting a heavy sack of grain onto one’s shoulders) as well as Hargrave’s own fascination with the “magical nature” of the letter K.

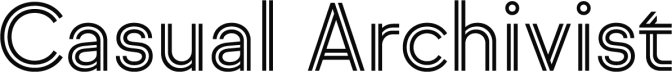

The Kibbo Kift produced a wide range of artistic objects, both for organizational use (uniforms, insignia, etc.) and as a natural extension of their focus on handicraft. For members, craft was both leisure and discipline; a creative pursuit as well as a way to toughen body and mind and prepare for a post-collapse world. Across the short 15 years the group was active, members created a staggering number of masks, banners, tents, carved totems, painted staffs, embroidered garments, publications, and sculptures. The aesthetic of these materials was a deliberate collage of the archaic and the modern: Saxon runes and Celtic knots sat beside Egyptian sunbursts, Native American totems, and abstract Modernist patterning. This symbolic bricolage created what Hargrave framed as a kind of invented “indigeneity”—a pseudo-native Englishness that borrowed freely from global traditions in order to construct legitimacy and offer a symbolic identity separate from the empire.

The work of the Kibbo Kift was highly symbolic. Similar to the Dutch De Stijl movement, where codified design represented a larger system of thought, the visual forms of the Kibbo Kift attempted to enact ideology literally. Visual motifs weren’t treated as decorative afterthoughts, but as mini manifestos. Like a hieroglyph or a rune, their forms carried meaning both separate from and in tandem with language. Kibbo Kift costumes, regalia, and even campsite layouts were imagined as a “magical imprint,” a total environment meant to implant ideas in the psyche and give coherence to a sprawling Utopian agenda. This sensitivity to the power of aesthetics was embedded in the group’s leadership; Hargrave worked professionally as a commercial designer and illustrator in the 1920s, producing layouts for clients like soap manufacturer Lever Brothers (later acquired by Unilever) and the publisher Mills & Boon, and understood the psychology of mass persuasion and the power of visual coherence.

You can still find echoes of Hargrave’s peculiar sacred forms if you keep your eyes peeled: the 2024 launch video for Teenage Engineering’s Medieval synth references them, as has high fashion, installation art, environmental activism, and even the work of Judy Chicago and A24’s Midsommar, if you’re feeling charitable. While Kibbo Kift’s motifs may look eccentric now, their rituals, symbols, and costumes functioned much like a brand—a visual system that signaled belonging and values, and that sold people a vision of a better world. In short: the Kibbo Kift lives on!